Grande Fantasia Imperiale

The New Roman Empire vs. the British Empire, 1940

A Wavell’s War Hypothetical Historical Scenario

by John M. Astell

Copyright 2013. All rights reserved. Do not distribute in any form without express permission of the author!

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: Rules

- Part 3: Orders of Battles

- Part 4: Final Notes

Please Consider Donating

This scenario is free to use for personal use. If you enjoy the scenario, please consider making a small donation. Thank you!

Final Notes

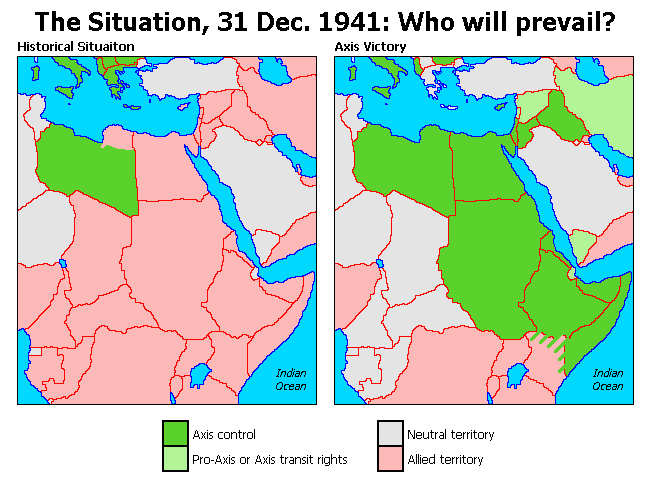

In 1940, the Axis missed its best opportunity to defeat the British Empire in northeastern Africa and western Asia. With the surrender of France, the British loss of most of its modern military equipment at Dunkirk, and the need to defend Britain against a potential German invasion, the British had little military resources left during the summer of 1940 to defend its interests elsewhere. Indeed, Australian and New Zealander troops intended for the Middle East were diverted to Britain to bolster its defenses. Only after the Battle of Britain was won and the German invasion threat faded could Britain start to significantly reinforce its forces overseas.

At the same time, the Axis had military forces, particularly mechanized formations, readily available for use. The Grande Fantasia Imperiale scenario examines what would have happened had the Axis seized its chance, rather than frittering away its opportunity through inaction and ill-advised ventures like the invasion of neutral Greece. The scenario avoids excessive use of hindsight—the Axis did not know in advance that France would fall so quickly or that the British would lose their equipment, so the scenario does not start with a massive Axis armored army poised on the borders of Egypt. Instead, the Italian and German mechanized divisions trickle in throughout the summer. Overall, the scenario commits all three of Italy’s armored divisions (all of which historically went to Africa in 1941-42), both of Italy’s motorized infantry divisions (both of which historically went to Africa in 1941), and all three of Italy’s semi-motorized infantry divisions (which historically were used in other theaters). Germany’s contribution consists of the Deutsches Afrika Korps with two panzer divisions and one motorized infantry division—overall, a slightly smaller force than was committed historically in 1941.

The Luftwaffe is heavily committed against Britain until late 1940, leaving just the Regia Aeronautica to support the troops and bomb Malta. An extensive bombing campaign against Malta, however, may not be necessary. The Italian armed forces knew well before the war that the British colony of Malta had the potential to disrupt any Italian war effort in Africa, and they had invasion studies dating back to the mid 1930s, when Britain’s relations with Italy soured over the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. The scenario allows the Axis to attempt an invasion in both 1940 and 1941—although any 1940 invasion is an Italian-only affair until late 1940, when German air and airborne are released after the cancellation of Operation Sea Lion. Like Britain, Malta will never be weaker than what it was in 1940.

The Italian forces in East Africa are, for a time, much more powerful than what they are in the Wavell’s War East Africa Campaign scenario of 1940-41. With the cut-off supply terminals rule and the slowly degrading of general supply abilities, the East African forces have several turns to rampage before severe supply problems set in. An Axis player should use these forces aggressively, just as historically the British feared would happen in mid 1940.

The long term prospects of the Axis in East Africa, however, depend upon events in Egypt. The Axis need to use their superior forces to break into the Delta and attempt to seize the Suez Canal before the British can wreck it. In Wavell’s War, the Allies can always permanently close the canal—overall, by far the most likely case. However, under the chaotic conditions of an Axis breakthrough into the Delta, it is possible that a dash to canal might secure it before the British can block it extensively, so the rules allow a slim chance of this.

The British are initially very constrained in the scenario due to the need to defend Britain. After they win the Battle of Britain, the scenario assumes the likely critical situation in the Middle East will prompt the British to risk reinforcing the area a bit more than they did historically, at the expense of the forces for the defense of the UK.

For the main commands under the Allied player’s control, the Allied order of battle simplifies the arrival of forces and does not show many of the force transfers between these commands, unlike the War in the Desert OB. Historically, which command arriving and transferred forces went to often depended upon the military needs of the moment. Since it is likely that events in the scenario can diverge widely from historical, the OB allows the Allied player to allocate his forces as he thinks best.

Although not evident in the Allied OB, the neutrality of Greece is a bonus for the Allies in the spring of 1941. Historically, significant Allied strength was diverted from Africa to Greece for months and returned later with heavy losses. Also, Greek neutrality means the Axis does not capture Crete and use its airbases to threaten the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. The drawback to all this, however, is that Axis gains in 1940 may make these 1941 Allied “advantages” moot.

For convenience, the orders of battle use counters available in existing games, particularly War in the Desert. Historically, some British units would not have been ready for overseas operations in 1940/41. Similarly, some German units, particularly the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions, did not exist at the time they appear in the scenario. Using these units rather than identically rated units with different unit IDs requires fewer new counters. (OB purists could note that mid 1940 panzer divisions were organized differently than those in 1941, but the scenario assumes a special “Africa service” organization is adopted for the panzer divisions sent there, which essentially was the case in 1941.)

Wavell’s War was designed for scenario start dates in the period September-December 1940 and with certain assumptions, like Italian East Africa being cut off, built in. These are good decisions for that game, but they had to be adapted or generalized to handle the needs of this scenario, which has an earlier start date and a greater range of possible events.

The scenario stops at the end of 1941. With a year and a half of operations, it should be possible to judge how well the Axis has done in conquering this area of the world. If you want to continue on, feel free (just make sure you don’t take as reinforcements in 1942 units that the scenario gave you in 1940!).

The North Africa map group was not included in the game, partly to save space. You can add them if you wish (just adjust the Italian Tripolitanian garrison accordingly). If you do play on into 1942, you will need these maps. In some ways, Axis success in this scenario may make the Allied invasion of French North Africa more effective than historical. With, say, Axis forces fighting in Iraq and East Africa, its hard to see how Rommel and the DAK can get to Kasserine in time to counterattack!

After considerable thought, the Near East map group was included, so that Iraq can be shown. While the Italians were looking more to the south to Kenya than east to Iraq, the scenario assumes the Germans would be interested in Iraq, securing a route to friendly Iran, and potentially creating a threat on the southern border of the USSR. The Germans are assumed to react quicker than historically to an Iraqi coup and more forcefully, with special forces and a small mountain corps. Still, for a smaller scenario, you can dispense with the Near East (just don’t receive the German Near East Corps even if triggered).

Enjoy!

—John M. Astell

Appendix

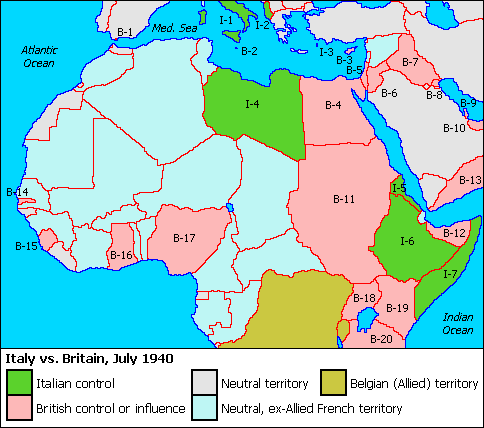

Mediterranean and Northeastern Africa, July 1940

British Controlled or Influenced Territories, July 1940

B-1 |

Gibraltar |

B-11 |

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan |

B-2 |

Malta |

B-12 |

British Somaliland |

B-3 |

Cyprus |

B-13 |

Aden |

B-4 |

Egypt |

B-14 |

The Gambia |

B-5 |

Palestine |

B-15 |

Sierra Leone |

B-6 |

Transjordan |

B-16 |

The Gold Coast |

B-7 |

Iraq |

B-17 |

Nigeria |

B-8 |

Kuwait |

B-18 |

Uganda |

B-9 |

Qatar |

B-19 |

Kenya |

B-10 |

Trucial States |

B-20 |

Tanganyika |

Italian Controlled Territories, July 1940

I-1 |

Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia) |

I-5 |

Eritrea |

I-2 |

Albania |

I-6 |

Ethiopia |

I-3 |

Dodecanese Islands |

I-7 |

Italian Somaliland |

I-4 |

Libya |

||

British On-Map Controlled or Influenced Territories, July 1940

Notes:

- After World War I, the League of Nations created mandates that allowed various great powers, such as Britain, to administer various territories, including some in the list below. While the mandates officially did not make these territories colonies of the mandatory powers (typically, the territory was eventually supposed to become an independent nation), the mandate granted very wide latitude to the mandatory powers to govern the territories as they wished.

- Various territories below are referred to as colonies while others are called protectorates. Theoretically, the difference between the two was that a country had outright sovereignty over its colonies but in a protectorate served as the protecting power for the local rulers, who retained sovereignty. In practice, many (not all) protectorates were run by the protecting power just like a colony. Particularly in Africa, some territories were both a colony and a protectorate—typically a colony along the coast, established centuries ago, with the inland regions a protectorate established in the 19th Century.

B-1 |

Gibraltar: British colony. Gibraltar was captured from Spain by British forces in the early 18th Century and was ceded in perpetuity to Britain in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. It became a British crown colony in 1830. Fortified, with a good harbor, and located on the Straits of Gibraltar separating the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, Gibraltar was an important base for the Royal Navy. In World War II, the civilian population was evacuated (until 1944) and Gibraltar served as a crucial Allied naval base and fortress, as well as an airbase for Operation Torch. Gibraltar was a target of occasional Axis air raids and Italian frogman special operations. German forces planned to assault and take the fortress in 1941, but this did not occur when Spain refused to allow German forces to operate on its territory. The Gibraltar Defence Force was recruited from the inhabitants of the colony and helped defend the Rock in artillery, antiaircraft, and specialist units. |

B-2 |

Malta: British colony. Britain gained possession of Malta in the Napoleonic Wars. The French had seized the island from the ruling Knights of St. John*, but the Maltese soon rebelled and called in British assistance. Malta became a British crown colony in 1814. The harbor at Valletta became a useful base for the Royal Navy, and Malta became an important way station between Britain and India after the Suez Canal opened. In World War I, Malta as a base helped support Allied operations in the eastern Mediterranean. In the Second World War, Malta was in the active war zone when Italy entered the war in 1940. As a vital base between Italy and North Africa, the British used Malta to disrupt Axis shipping to Africa, while the Axis extensively bombed the island and attempted to starve it into submission. An Axis airborne and amphibious invasion of Malta was planned in 1942 but not executed. Once the Allies won the Battle of El Alamein in Egypt and Allied forces invaded French North Africa, the Axis threat to Malta quickly passed. *The Knights of St. John were also known as the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, the Knights Hospitaller, the Knights of Rhodes, the Knights of Malta, and the Cavaliers of Malta. The order remained in existence after their expulsion from Malta. Reorganized as the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta, it is better known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. The group today has observer status at the United Nations. |

B-3 |

Cyprus: British colony. The Ottoman Empire conquered Cyprus, a Greek-speaking Christian island and Venetian possession, in the 16th Century, and Turkish-speaking settlers came to the island. In 1821, when Greeks in some other parts of the Ottoman Empire revolted and eventually established an independent Greece, the Ottomans quickly suppressed the secret society on Cyprus working for Greek independence. Later in the 19th Century, the expansion of the Russian Empire threatened the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and created competition between Britain and Russia. This led the Ottomans to lease Cyprus to Britain as a base and counterweight to Russia. As fate would have it, World War I saw Britain and Russia on the same side against the Central Powers, which the Ottoman Empire joined in late 1914, whereupon Britain formally annexed the island. During the war, the British used Cyprus as a base against the Ottomans and offered to unite it with Greece should Greece declare war on the Central Powers. Greece refused, and the offer was withdrawn. Cyprus became a British crown colony in 1925. Relations between the British and the two Cypriot communities were often strained, as the Turkish-speaking population underwent growing Turkish nationalism following the creation of the Republic of Turkey, while the Greek-speaking population favored unification with Greece. In 1931, riots by Greek radicals were suppressed. In World War II, Cyprus served as an important base for British operations in the eastern Mediterranean. In 1941, the British increased the garrison of Cyprus to divisional strength to protect the island from a possible Axis invasion. The Axis had made some plans for an invasion, but neither Germany nor Italy seriously contemplated executing them. Instead, the Germans attempted to foment unrest among the Cypriots, with little apparent success. |

B-4 |

Egypt: Independent nation with various concessions to Britain. In the early 16th Century, the Ottoman Empire conquered Egypt, a Muslim land. They placed a series of Ottoman-appointed governors (pashas) over the Mamluk princes (beys) who were the former rulers and who continued to control the Egyptian provinces. Over time, Ottoman control of Egypt weakened and the beys grew unruly. Eventually, the pashas most of the time had little real authiority over Egypt, while Mamluk factions competed against each other for power and treasure. In the Wars of the French Revolution, the French invaded Egypt and defeated the Mamluks, but the French were later defeated by the Ottomans and British. After the French surrender, the Ottomans appointed Muhammad Ali, an Ottoman commander and Albanian Muslim, as pasha of Egypt. However, Ottoman control was still weak, and Ali acted with considerable autonomy—essentially independent. Ali extinguished Mamluk power in Egypt and introduced Western-style political, economic, and social reforms. Under Ali, Egypt grew in power, becoming a virtual empire-within-an-empire with control over territory from Syria to northern Sudan. At one point, Ali was on the offensive against his nominal Great Sultan (or Padishah) and may well have taken over the entire Ottoman Empire. The opposition of the European great powers resulted in him abandoning the war in return for his line becoming the hereditary pashas of Egypt. Ali’s descendants and successors, alas, did not rule well. Egypt plunged into international debt, through ventures like Egypt’s involvement in the French building of the Suez Canal and the pasha's expenditures to obtain a loftier title, Khedive, from the Ottomans. (Khedive is often translated as or equated to “viceroy” although this is perhaps not the best sense. "Ruler" may be a better equivalent term.) Financial problems led the Khedive to sell his stake in the canal to the British and then to accept a French-British Debt Commission with considerable power over his state. Revolts within Egypt in the early 1880s allowed Britain the pretext to occupy Egypt and administer it as if it were a protectorate, which Britain later outright proclaimed in 1914 when the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers. In that war, the British successfully used Egypt as a base for operations against the Ottomans, while the Ottomans unsuccessfully tried to dislodge the British from the Suez Canal. Egyptian nationalists, however, did not favor British rule. After the war the British and Egyptians agreed to a treaty that recognized Egypt as a independent nation under a king. However, the treaty granted Britain a number of rights including the ability to station military forces in Egypt. Egypt became a war zone in World War II because of the presence of British forces there. Axis forces fought the British in Egypt and nearby Libya until the Axis was defeated in North Africa in 1942-43. Egyptian forces did not participate in the war, nor did Egypt declare war against the Axis nations until 1945, so as to become a founding member of the United Nations. |

B-5 |

Palestine: British League of Nations mandate. In the World War I campaigns against the Ottoman Empire, British forces occupied the Palestine region, which included territory both west and east of the Jordan River. During the war, the Allies had made a number of conflicting understandings that affected the region: 1) the Hussein-McMahon correspondence in which the British promised support for an Arab independent state in return for an Arab revolt against the Ottomans; 2) the Balfour Declaration of British support for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine; and 3) the Sykes-Picot Agreement between Britain and France which divided the region between the two countries. After the war, Britain received a League of Nations mandate for Palestine, with provisions that a Jewish national home be established in Palestine and that "nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine." Britain attempted to partially fulfill its conflicting understandings by creating a Arab state in the region east of the Jordan River (see B-6, Transjordan, below), allowing Jewish immigration in the western region, and keeping actual control for itself. Jewish immigration to the area created growing resentment in the Arab population of the region, resulting in the Arab Revolt of 1936-39. Britain put down the revolt by force and then restricted Jewish immigration in Palestine, which of course was resented by the Jewish population. In World War II, relations between the British and Jews improved, as both sides desired the defeat of Nazi Germany. Cooperation greatly increased in 1942, with the Axis threatening to overrun Egypt and occupy Palestine. Both Jews and Arabs served in British Palestine support and service units. Late in the war, a Jewish combat unit, the Jewish Brigade, was organized in the British forces and served in Italy. After the war, the British withdrew, the state of Israel was proclaimed on part of the territory, and the Arabs and Israelis have been fighting over the fate of the region every since. |

B-6 |

Transjordan: Arab emirate; autonomous portion of the British League of Nations mandate for Palestine. See the first paragraph of B-5 above for introductory details. The mandate for Palestine included territory both west and east of the Jordan River. However, the mandate allowed Britain to exclude the Jewish national home from area east of the Jordan River. Britain did this, calling the area west of the river “Palestine” and the area east of the river “Transjordan” (or “Trans-Jordan”). The two areas were run as if they were separate mandates (although officially Transjordan was part of the Palestine mandate). In an attempt to satisfy Arab demands for an independent state per the Hussein bin Ali-Henry McMahon correspondence, the British made Hussein’s son, Abdullah, emir of Transjordan. The emirate had considerable autonomy but not independence. Transjordan had two small military forces, both under British officers: the Arab Legion (which the Arabs called Al Jeish al Arabi, “The Arab Army”) and the Transjordan Frontier Force. During World War II, small contingents of both forces were used in the 1941 British operations against Iraq and Syria, and both served as security forces and back-up defense forces in the Near East. After the war, Transjordan became a fully independent kingdom and later changed its name to Jordan. |

B-7 |

Iraq: Independent nation with various concessions to Britain. During World War I, British forces captured the Mesopotamian region from the Ottoman Empire. After the war, the three Ottoman provinces there were combined as Iraq, a League of Nations mandate administered by Britain. The British selected another son of Hussein bin Ali (see B-6), Faisal, to become king of Iraq. In 1932, an agreement between Britain and Iraq resulted in Iraq became an independent nation, while Britain retained various concessions in the country including the transit and basing of military forces. Oil was discovered in Iraq in 1927 but significant extraction did not occur until 1938. During World War II, lack of shipping for a large portion of the war actually resulted in Iraqi oil production being greatly reduced. At the start of World War II, Iraq was neutral, but in 1941 a coup by anti-British, pro-Axis officers toppled the government. The British responded by occupying the country and restoring the pro-British government. In 1943, Iraq declared war on the Axis powers, although Iraqi forces did not fight the Axis. British forces continued to occupy Iraq for the duration of the war but withdrew after the war's end. |

B-8 |

Kuwait: British protectorate. Kuwait was an Arab emirate, nominally under the Ottoman Empire. Growing British presence in the Middle East in the 19th Century and Ottoman attempts to gain greater control of the region resulted in Kuwait becoming a British protectorate in 1899. At the time, the Kuwait economy was dominated by pearl harvesting, but the emirate became impoverished in the 1930s with the effects of the Great Depression and, especially, the production of cheap cultured pearls in Japan. Oil was discovered in Kuwait in 1938 but mass extraction did not occur until after World War II. During the war, Kuwait was an important British base in the Persian Gulf region. The protectorate ended in 1961 and Kuwait became fully independent. |

B-9 |

Qatar: British protectorate. Nominally under the Ottoman Empire, Qatar and the entire Arab coast region of the Persian Gulf were ruled by essentially independent local sheiks. British interest in the region grew due to its location near British India. In 1916, during World War I, Britain made Qatar a protectorate. Like Kuwait, Qatar was impoverished when the local peal industry was devastated by cheap Japanese cultured pearls. Oil was discovered in 1939 but not exported until after World War II. The protectorate ended in 1971 with full independence. Bahrain: British protectorate. Another nominal Ottoman dependency, Bahrain was ruled by a local Arab family. In the 19th Century, a series of treaties with Britain made Bahrain a protectorate of Britain. Oil was discovered in 1931, as the pearl industry was collapsing, and oil exports began in 1932. The protectorate ended in 1971 with Bahrain's independence. |

B-10 |

Trucial States: British protectorates. Nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, the sheikhdoms along the southeastern Persian Gulf were effectively independent and supported piracy to such an extent that the region was known as the Pirate Coast. This attracted the attention of Britain in the 19th Century, and a series of treaties or “truces” between Britain and these “Trucial States” led to the Perpetual Maritime Truce in 1853. In an 1892 treaty Britain promised them military protection and took over the states’ foreign relations. The area was a backwater during World War I, due to British predominance there. After the war, the region, like many places in the Persian Gulf, struggled economically because of the Depression and Japanese cultured pearls that devastated the local pearling industries. During World War II, the Trucial States were not in a war zone but were considered strategic naval and air bases for defending the Persian Gulf region if the Axis reached the area. Oil was not discovered here until after the war. In 1971 British control was withdrawn and the Trucial States federated as the United Arab Emirates. |

B-11 |

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: Officially a British and Egyptian “condominium” but effectively a British colony. In the 19th Century, an expansionist Egypt gradually gained control over much of the region that makes up modern Sudan, including the Gezira area south of Khartoum, a significant producer of what came to be called “Egyptian cotton,” and the Darfur sultanate west of Khartoum. However, Egypt fell on hard times and became a British protectorate. A Mahdist revolt in northern Sudan starting in 1881 led to expulsion of Egyptian and British forces from the region by 1885-86. This included Darfur, which had been restive under the Egyptians and remained rebellious to the Mahdists. In the 1890s, with growing French, Italian, and Belgian interest in eastern Africa, the British reasserted their claim to control the region. British forces defeated the Mahdists in 1898. Since the Sudan* was nominally Egyptian territory, in 1899, an Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (think “co-dominion”, not housing) formally established joint British and Egyptian administration of the region. Darfur was reestablished as a sultanate tributary to the Sudan and in effect was independent again. *Sudan was often called "the Sudan" before and during the World War II era, whereas "Sudan" began to be used more frequently after the war. A bit confusingly, "the Sudan" is also a geographical region of land south of the Sahara desert, stretching across the African continent. This article uses "the Sudan" for the territory, not the greater region, for historical context. In World War I, the Sultan of Darfur declared loyalty to the Ottoman Empire. The British reacted quickly by defeating his forces and incorporating the Darfur region into the Sudan. After the war, Britain transferred territory from northwestern Sudan to Libya, an Italian possession, as partial compensation for Italy joining the Allied side in the war. When Egypt became independent after World War I, tensions between Egypt and Britain over the Sudan grew. In 1924, a Sudanese mutiny, perhaps instigated by Egypt, occurred, and the British governor-general of the Sudan was assassinated in Cairo. Britain then forced Egypt to withdraw all Egyptian forces and officials from the Sudan and effectively ran the Sudan as a British colony. During World War II, small portions of the Sudan briefly suffered Italian incursions from Italian East Africa, but the Axis threat was soon eliminated by the British conquest of Italian East Africa. Sudanese forces under British officers served in East Africa and North Africa. After the war, Egypt and Britain eventually abandoned their claims to the Sudan, which became independent in 1956. The southernmost portion of Sudan became independent as South Sudan in 2011. This region, mainly inhabitated by black Africans while the rest of Sudan was mainly Arab-inhabitated, was conquered by Egypt in the 19th Century and subsequently remained an isolated backwater of the Sudan thereafter. While officially part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, the British essentially ran the southernmost region as a separate colony. After World War II, the British explored uniting most of this region with Uganda (and a part of it to the Belgian Congo), but this did not occur and all of the area of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan became the unitary state of Sudan. However, even before formal indendence, it became clear that the Arab north was going to run the entire country with little input from the black south, which provoked unrest and led to the north-south civil wars that eventually ended with the independence of South Sudan. |

B-12 |

British Somaliland: British protectorate. The British became established in the area after seizing Aden (see B-13), with the Somali areas across the Red Sea being used to supply the Aden garrison with food. As European powers expended into the region later in the century, the British organized British Somaliland as a protectorate. In World War II, the protectorate was conquered by Italian forces from Italian East Africa but was soon retaken by British forces during their East African campaign. In 1960, British rule ended with the territory joining the former Italian Somaliland to form the independent nation of Somalia. When central government of Somalia ceased functioning in the late 20th Century, the area of the former British Somaliland proclaimed itself the independent country of Somaliland. Although not internationally recognized as independent, Somaliland to the present is mainly peaceful and prosperous, unlike the rest of Somalia. |

B-13 |

Aden: British colony and protectorate. The British became established in the area after seizing the port city of Aden during Red Sea anti-piracy operations in 1839. Subsequently, nearby areas along the southern coast of the Arabian peninsula became a British protectorate, while the city itself eventually became a British crown colony. Aden became an important way station between Britain and India, and its importance increased once the Suez Canal opened. Aden was an important Royal Navy base in both world wars. In the 1960s, the territory began a somewhat convoluted process of obtaining independence (with two British-ruled organizations, the Federation of South Arabia and the Protectorate of South Arabia co-existing for some years), until the region became fully independent in 1968 as South Yemen. |

B-14 |

The Gambia: British colony and protectorate. British presence in the Gambia River region dates back to 16th Century English trading posts, which developed into a crown colony. The narrow, winding shape of the colony resulted from a 19th Century French-British agreement that the British sphere of influence in the region comprised the area within cannon range of gunboats on the Gambia River. Britain then declared a protectorate over the land within its sphere but outside the established colony. An imperial backwater in both world wars, colonial troops from the Gambia fought for Britain both wars. The Gambia gained independence in 1965. |

B-15 |

Sierra Leone: British colony and protectorate. “Sierra Leone” (Lion Mountains) derives from the name Portuguese explorers called the region, Serra Lyoa. Like much of British West Africa, British presence here goes back to 16th and 17th Century English trading posts, which developed into colonies. Freetown, which became the principle city of the region, arose from the 18th Century settlement of freed slaves from the Americas. The city later became a major Royal Navy base in the fight to abolish the African slave trade. As with The Gambia, French-British agreements over West African spheres of influence resulted in Britain proclaiming a protectorate over the Sierra Leonean territory within the sphere but outside the colony. Colonial troops from Sierra Leone fought for Britain both wars. Sierra Leone became independent in 1961. |

B-16 |

The Gold Coast: British colony. The British established trading “factories” and forts in West Africa in the 17th Century and gradually expanded their control in the region, famous for its gold resources. The region, called the Gold Coast, first became a British protectorate and then a British colony. After World War I, the Gold Coast became an important source of cocoa. The Gold Coast was a backwater in World War II, as there were no Axis forces or possessions in West Africa. The Gold Coast, together with nearby British Togoland (see below) became the independent country of Ghana in 1957. British Togoland: British League of Nations mandate. In World War I, the German protectorate of Togoland was quickly conquered by Britain and France, with its territory divided in British Togoland, administered by Britain, in the east and French Togoland (Togoland Français, also called Togo oriental) in the west. After the war, Togoland became a divided League of Nations mandate, with the British still running the western region, British Togoland, and the French the eastern region, French Togoland. Although British Togoland was a mandate and the Gold Coast was a British colony, the British administered them jointly, with the result, just perhaps unintended, that British Togoland came to have somewhat more in common with the Gold Coast than with French Togoland. Like the Gold Coast, British Togoland was a backwater in World War II. After the war, British Togoland became a United Nations trust territory but was still run by Britain and administered jointly with the Gold Coast. In 1956, British Togoland voted to join the Gold Coast, and in 1957 the Gold Coast and British Togoland officially merged and became the independent country of Ghana. |

B-17 |

Nigeria: British colony and protectorate. While much of western Africa began to fall under control of European countries in the 16th and 17th Centuries, it was only in the 19th Century that the region which is now Nigeria came under European rule. Over the second half of the century, the British established a coastal colony at Lagos, created two protectorates in nearby territory, and chartered the Royal Niger Company, which economically exploited the lower Niger River and also gained control of futher territory in the region. After a number of reorganizations, the takeover of the British Niger company by the British government, and wars to defeat local resistance to the British, in 1914 these territories were merged as the Protectorate and Colony of Nigeria. After World War I, portions of the German colony of Kamerun were added to Nigeria. In World War II, Nigeria provided a number of Colonial troops to the British war effort. Nigeria gained its independence in 1960. |

B-18 |

Uganda: British protectorate. In the late 19th Century, Germany and Britain competed for influence over the kingdom of Bugunda. In 1890, an agreement defining British and German interests in Africa resulted in the kingdom being assigned to the British sphere. (As part of the treaty, the British-controlled Heligoland island in the North Sea off the coast of Germany was ceded to Germany and soon became a massive fortress guarding Germany from the Royal Navy in the two world wars.) Buganda plus surrounding territory became the Uganda Protectorate. Uganda became independent in 1961. |

B-19 |

Kenya: British colony and protectorate. Kenya Protectorate was the coast strip including Mombasa, held by Britain on behalf of the Sultan of Zanzibar. Kenya Crown Colony was the interior region. In 1926, as a partial fulfillment of World War I territorial promises to Italy, the Somali-inhabited Jubuland region was ceded to Italy and was incorporated into Italian Somaliland. Kenya’s North Frontier District also had a Somali population, which would be a cause of tension between Kenya and Somalia after World War II. During the war, Kenya was used as one of the bases for the British invasion of Italian East Africa. Kenya gained its independence in 1963. |

B-20 |

Tanganyika: After World War I, most of the German colony of German East Africa became the Tanganyika Territory, administered by Britain under a League of Nations mandate. (The Ruanda-Urundi region went to Belgium as a League of Nations mandate and eventually became Rwanda and Burundi.) In World War II, after the fall of Malaya to the Japanese, the territory became an important source of rubber for the Allies. Tanganyika became independent in 1961, and within a few years joined with Zanzibar to form the country of Tanzania. |

Italian On-Map Controlled Territories, July 1940

I-1 |

Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia): Technically a constitutional monarchy but in actuality a fascist dictatorship. The Kingdom of Italy (Regno d’Italia) came into existence in 1861 when most of the states and provinces on the Italian peninsula were unified, with the king of Sardinia, Victor Emmanuel II, becoming the king of Italy. Austrian-controlled Venice was united with the kingdom in 1866 (the year Prussia defeated Austria-Hungary in a war), and the Papal States were united with the kingdom in 1870 (when the French withdrew their forces from Rome during the Franco-Prussian War). Rome became the capital city of Italy in 1871. Unified Italy was irredentist—desiring to liberate Italian-populated regions outside of Italy’s borders (Italia irredenta, unredeemed Italy)—and expansionist—desiring to obtain overseas colonies like the other great European powers. This led Italy into a series of wars and intrigues, with the successful acquisition of various territories in Africa and the Aegean but also a humiliating defeat of an Italian invasion force by Ethiopia in 1896. Italy initially declared neutrality in World War I, but joined the Allies in 1915 when promised territories, particularly the Italian-populated regions of Austria-Hungary. However, the treaties at the end of the war awarded Italy only a small portion of what it had expected. This alienated many Italians from their former allies. After the war, with its huge human and economic toll, Italy experienced unrest and political upheaval. In this foment, Benito Mussolini formed the Fascist Party in 1919 and marched on Rome in 1922, with the Italian king then appointing Mussolini as prime minister. Within a few years, Mussolini and Fascists turned Italy into a dictatorship under “Il Duce” (the Leader). In the 1930s, Fascist Italy aided Franco in the Spanish Civil War, conquered Ethiopia and Albania, and reached an accord with Nazi Germany, forming the “Rome-Berlin Axis.” With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Italy at first was neutral but pro-German. In June 1940, with France on the verge of defeat, Italy entered the war on Germany’s side. The war did not go well for the Italians, however, and a growing string of defeats on all fronts from late 1940 to mid 1943 caused Italy to surrender to the Allies. Italy later declared war on its former ally, Germany, while the Germans set up an Italian puppet government under Mussolini in northern Italy. Italy remained a bitterly fought theater of war until German forces there surrendered to the Allies in April 1945. That month, anti-Axis Italian guerrillas captured and executed Mussolini. In 1946, a referendum abolished the monarchy, which was now unpopular because of its acquiescence to the Fascists in 1922-1943, and established Italy as a republic. |

I-2 |

Albania: Italian occupied territory. The Ottoman Empire gained control of Albania in the 15th Century but never fully subjugated the highland regions. In the 19th Century, Albanians increasingly became nationalistic, as the Ottoman Empire weakened and lost control of nearby areas like Greece, Romania, Serbia, and Bulgaria. Albania proclaimed independence in the First Balkan War of 1912, was occupied by Serbia in the Second Balkan War of 1913, and was then recognized as an independent monarchy in the post-war settlement engineered by the European great powers. However, several Albanian majority- and minority-inhabited regions were incorporated into the nearby states of Montenegro, Serbia, and Greece. Soon after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the weak Albanian state collapsed, and the country became a battleground for the warring powers. After the war, Albania regained its independence but experienced considerable instability, with Italy and Yugoslavia competing to dominate the country. In the mid 1920s, with Yugoslav assistance, Ahmed Zogu gained control of Albania, but soon favored Fascist Italy over Yugoslavia for assistance. Zogu later proclaimed a monarchy with himself as King Zog. Italian influence continued to increase, until Italy invaded and conquered the country in early 1939. Officially, this was a “personal union” of the Italian and Albanian monarchies with the Italian king becoming the king of Albania, and a local Albanian government was formed. In actuality, the Albanian government was a puppet controlled by Mussolini, and the country was Italian occupied territory. During World War II, Italy would use Albania as a base for the invasion of Greece. Italian control over Albania was not secure, with growing resistance and guerrilla movements, particularly a Communist movement after the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Germany occupied the country when Italy surrendered in 1943 but gradually lost control of the countryside to the Communists and withdrew from the region in late 1944. Albania was perhaps the only Axis-occupied area in Europe to free itself without any direct military intervention from outside powers. (Even Yugoslavia, the majority of which was freed by its own efforts, was aided by a Red Army intervention around Beograd in 1944.) During 1944, the Albanian Communists formed a provisional government for the country and soon transformed the country into a "socialist republic" (Communist dictatorship). |

I-3 |

Dodecanese Islands: Italian colony. The Ottoman Empire conquered the Greek-inhabited Dodecanese Islands from the Knights of St. John (see B-2 for more details on this order) in the 16th Century. The islands were granted considerable autonomy within the empire, provided that they submit to Ottoman rule. The Dodecanese did not join the 19th Century Greek War of Independence that led to the creation of independent Greece, although the population was strongly pro-Greece. In 1912, while the Ottoman Empire was involved in both the First Balkan War and the Italian-Turkish War, the islands declared independence but were quickly occupied by Italy. Although Italy agreed to hand them back to the Ottomans eventually, Italy instead officially annexed them after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. (One island, Kastellorizo [Castellorizo in Italian] had not been occupied by Italy in 1912-15 but was annexed by Italy after World War I.) The islands became an Italian colony, officially the Italian Islands of the Aegean, Isole Italiane dell'Egeo, although they were informally known by other names, including the Colony of Rhodes, Colonia di Rodi. The islands were used as Allied bases during World War I and as Axis bases in World War II, with Germany occupying them following Italy’s surrender. German occupation lasted until the end of the war in 1945. In the Italian peace treaty of 1947, the islands were ceded to Greece. |

I-4 |

Libya: Officially, an integral part of Italy; in actuality, an Italian colony. The Ottoman Empire gained control of the coastal regions of Libya (Tripolitania and Cyrenaica) in the 16th Century and extended its sway to the interior (the Fezzan) in the 19th Century, organizing the region as the province of Tripoli. Ottoman rule tended to be very light and at times non-existent. Local rulers made Tripoli a bastion of piracy and tribute-seeking, leading to clashes with European powers and the young United States of America (the origin of “the shores of Tripoli” in the U.S. Marine Corps Hymn). Italy acquired the province of Tripoli from the Ottomans in the Italian-Turkish War of 1911-12 and formed it as the Colony of Libya (Colonia di Libia). The local population resisted the Italians, but the Italians had occupied much of the region by 1914. Libyans, particularly followers of the Islamic Sanussi movement, continued to oppose the Italians, who had to undertake numerous pacification campaigns to subdue the country. Under Mussolini, 40,000 Italian settlers colonized parts of Libya, particularly the mild Jebal Akhdar (Green Mountain) region of Cyrenaica, and in 1939 Italy declared Libya to be an integral part of Italy, Italian Libya (Libia Italiana), similar to how France had declared Algeria to be an integral part of France. The local Muslim population, however, did not receive full Italian citizenship, and Libya to all effects remained a colony. Libya was a battleground in World War II, falling to the Allies in 1942-43 and being placed under British and French military administration. Libyans fought for both sides in the war, as regulars in Libyan units of the Italian Army and mostly as irregulars and auxiliaries in the anti-Italian “Sanusi Army” organized by Britain. British and French administration ended in 1951 with Libya gaining full independence. |

I-5 |

Eritrea: Part of Italian East Africa, an Italian colony. In the late 19th Century, Italy took control of this territory on the Red Sea and organized the region as the Colony of Eritrea (Colonie Italiana Eritrea). After the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in the 1930s, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Italian Somaliland were merged together as Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana), an Italian colony. In 1941, the British occupied the territory and placed it under British military administration. Eritrea later became a UN mandate under British administration until 1951, when it federated with Ethiopia (and later became independent). |

I-6 |

Ethiopia: Part of Italian East Africa, an Italian colony, then independent country. Ethiopia (called Abyssinia by various western nations in the 19th and early 20th Centuries) was an independent empire in East Africa. Having crushed an Italian invading force in the Battle of Adowa in 1896, Ethiopia became a target for Italian expansion under Mussolini. In 1935-36, Italian forces invaded and conquered the country, with the emperor, Haile Selassie, fleeing to Britain. The Italians merged Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland together as Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana), an Italian colony, with the Somali-inhabited Ogaden region of Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland becoming a single province, Somalia. In 1941, British forces defeated the Italians there. After a period of British military administration, the empire through treaties in 1942 and 1944 regained its full independence, although its Ogaden province continued to be administered by the British until after the war. |

I-7 |

Italian Somaliland: Part of Italian East Africa, an Italian colony. In the 19th Century, the Italians leased portions of the southeastern Somali coast from the Sultan of Zanzibar, later annexing the territory outright and expanding along the coast and interior to form Italian Somaliland (Somalia Italiana), a colony. In 1926, as partial settlement of World War I promises, the Somali-populated Jubaland region was transferred by Britain from Kenya to Italy and incorporated into Italian Somaliland. After the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in the 1930s, Italian Somaliland, Ethiopia, and Eritrea were merged together as Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana), an Italian colony, with the Somali-inhabited Ogaden province of Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland becoming a single province, Somalia. In 1941, the British occupied the territory and placed it under British military administration for the rest of the war, including the Ogaden, which did not revert to Ethiopian control until after the war. After the war, Britain administered the area until 1949, when it became a UN trusteeship under Italian administration. In 1960, the former Italian Somaliland joined with the former British Somaliland to form the country of Somalia. |

Note |

Corsica: Part of metropolitan France. Corsica, the island north of Sardinia, was still under control of the French government (Vichy France) in July 1940, and Italy did not occupy the island until November 1942. |

Part 1: Introduction Part 2: Rules Part 3: Orders of Battles Part 4: Final Notes