Pytor the Great: In War, in Peace, and in Cruelty

Pyotr realized his country needed to be modernized and reformed, as it was being held back by excessive adherence to old traditions and customs. This was particularly prevalent among the Russian nobility, as the old ways entrenched their power at the expense of the Tsar and Emperor. Despite resistance and revolt, Pyotr largely succeeded in making the nobles subservient to him.

Pyotr used the example of prosperous western Europe for his reforms. Government was reorganized for better efficiency, with taxes reformed to bring in greater revenues. Education was improved at many levels, with the Sankt-Peterburg Academy of Sciences (now the Russian Academy of Sciences) being founded. Policies favoring mining, industry, and trade strengthened the Russian economy, with foreign trade greatly increasing. Pyotr also had the Russian alphabet modernized and the Russian calendar reformed to the Julian calendar. (The Gregorian calendar was better but was associated with the Catholic Church and thus was ignored for a long time by most Protestant and Orthodox lands.) He also founded the first Russian newspaper and frequently composed articles for it, particularly about his military victories and diplomatic accomplishments.

Pyotr's reforms increased his own power and the prosperity of Russia, which also benefited him. He was not interested in reforms that would benefit the common people for their own sake. For example, he increased the subjugation of Russian serfs, even though serfdom had been abolished in the western European countries he admired and mostly emulated.

Comments

The Azov Project

Many people know about Pyotr's grand project to build a new capital city from scratch in newly-conquered swamplands by the Baltic Sea. This was Sankt-Peterburg, called Pyotr's "window on the West" since access to the Baltic Sea made communications and trade practical with western European countries. Few people know that this was Pyotr's second grand development project. The first was building fortifications, a port, and a naval base from scratch in newly-conquered steppelands by the Black Sea, the Azov project.

Sea of Azov Region, 1695-1711

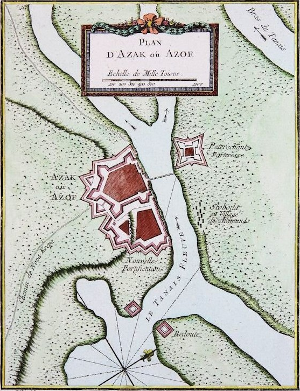

Pyotr I sought to gain access to the Black Sea by conquest. He fought two campaigns to conquer Azak, an Ottoman fortress on the Don River just a short ways inland on the Sea of Azov, a northeastern extension of the Black Sea. His first campaign in 1695 failed. Ottoman ships kept Azak supplied, and the Russians could not stop them. In 1696, he attacked again. His forces now included a fleet, which had been built in Russia using forced labor of 20,000 conscripted Russians. The ships sailed down the Don River to Azak while Pyotr's army marched there. The Russian flotilla forced the Ottoman fleet to withdraw, and the Azak fortress then fell to Russian land and naval forces. A garrison was established at Azov, as the Russian called Azak, which began rebuilding the damaged fortress.

Pyotr's Azov Flotilla became the start of a permanent Russian navy, with new, larger ships soon being built. However, forts and ships of the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire controlled the Kerch Straits, a narrow sea passage from the Sea of Azov to the main body of the Black Sea. It soon became evident that Russian ships would not be able to pass through the straits. Pyotr decided to develop his newly-conquered territory (called the Azov region in this work) into a Russian stronghold, as a base for future conquest. Waters off Azov fortress were too shallow for large ships, so a new site was selected to become a fortified naval base, trading port, and city. This became Taganrog, founded in 1698.

The Azov region was a new idea for Russian expansion. Previous expansion into the steppes had involved conquering a territory with the army, using troops and forts to secure the border against steppe warrior raids, colonizing the land with agricultural settlers, and building towns and a regional economy that were supported by the local agriculture. The Azov region was judged to be too difficult to defend from the steppe warriors, which meant widespread agricultural development was impractical. Instead, the plan was to build fortified enclaves along the coast and rivers, where settlers could hold out against steppe raiders and and be provisioned from Russian ships. Thus, the Azov region would be in effect like an oversea colony sustained by naval power.

The development effort was a huge rush project, including, in addition to the Azov region itself, a large shipbuilding effort and canal projects to connect the Don and Volga river systems. All told, at the height of the effort, about 50,000 workers were involved, perhaps 1 out of every 100 Russian workers, and almost 7% of the state budget was spent on the project in some years. While the Azov project was underway, Russian forces conquered Swedish territory on the Gulf of Finland, the easternmost extension of the Baltic Sea. In 1703, Pyotr began another grand project to fortify the region and to build a new capital city there, Sankt-Peterburg. Although this work competed with the Azov project for labor and money, the two projects were seen as complimentary, as they would be linked by rivers and canals spanning Russia from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. The straight-line distance from sea to sea was about 950 miles (about 1,500 km), but the travel distance via the canals and winding rivers would be hundreds of miles/km longer.

Pyotr recruited experts to help design and direct construction of Taganrog's fortifications, harbor, and city, from Austria, Italy, and Sweden. Since there was no local labor available, Russian serfs were sent there as involuntary workers. Thousands of soldiers were also sent there to garrison Taganrog. Their families were sent with them, effectively making them all involuntary settlers and another source of labor. Life in the new colony was very hard. The region had few trees, making it hard for the settlers, used to building in wood from Russia's extensive forests, to build housing and even to find enough firewood. Poor sanitation and overcrowding resulted in disease. After the first few years of settlement, about 60% of the soldiers and family members sent there had died, while another 20% of the soldiers had deserted and fled the region.

With conditions like these, the Azov region was always in need of fresh labor, and Russia met its needs with forced labor. The Azov region quickly surpassed Siberia as the preferred place to exile criminals sentenced to katorga, forced labor. The common people quickly learned of the harsh conditions at Azov from the many escapees returning home, just as they had earlier learned of the harsh conditions that exile to Siberia meant. It is suggested that some Russians became more law abiding in this period, to avoid being sent to Azov. It is certain that convicts exiled to Azov and workers conscripted to go there sought to escape their fate. In the winter of 1702-1703, for example, 312 carpenters were drafted in Moskva and sent to Azov under guard. 51 managed to escape during the first half of the journey, though the settled part of Russia. Much of the journey's second half was through unsettled steppe, and only another 11 escaped. However, 200 died during the second half of the journey, for reasons not recorded by their escorts. (Travelling through empty steppelands in the middle of the Russian winter, possibly with inadequate shelter and food, might explain the losses.) So, out of 312 carpenters, 62 ran away and 200 died, leaving just 50 arriving at Azov. However, another 14 soon died, likely from the hardships of the journey, leaving just 36 survivors, less that 12% of the carpenters who had set off.

Pyotr was well aware that his people did not want to go to Azov and would escape if possible. Rather than addressing the underlying problem, which would have required transforming the colony in a livable place, he resorted to ever harsher punishments, trying to deter the people's resistance. Punishments for attempting to escape included facial mutilation to mark deserters, public decimation (killing one deserter out of every ten caught), and criminalizing as traitors anyone who helped a deserter. This did not end resistance to going to Azov. Over time, Russian officials in many regions could only round up about half their quota of workers to be conscripted for Azov. Perhaps the officials did not try hard, as it seems likely many had a lucrative sideline in accepting bribes from those able to pay to avoid the draft. Of those who were too unlucky or too poor to avoid conscription, many of them deserted on the journey south. In 1709, the worse year (for the government, but the best year for the people), 98% of the 18,100 workers intended for Azov never arrived.

At Azov, government rules demanded that the laborers work 72 hours per week, at 12 hours per day for six days, even during the depths of winter. Katorga was a punishment for both civilian criminals (including those sentenced to death but sent into exile instead) and military criminals (deserters from the army, in particular), and often the criminal's entire family was sent into exile with him. This not only provided labor but also new settlers, for exile to Azov was supposed to be permanent. The need for labor resulted in the state expanding the range of crimes that could be punished with exile and katorga. When some Russian musketeers revolted in Moskva, Pyotr retaliated with mass executions of the revolters, with their sons, "underage musketeers", being sent into exile and katorga at Azov*. Foreign soldiers captured during Pyotr's many military campaigns were also sent to Azov. Soldiers from Sweden and the Baltic land knew how to farm and were required to farm the steppe outside the settlements. Many were taken as slaves in steppe warrior raids.

Since it was known from the start of the project that the steppe warriors would make farming impractical, why did Azov officials attempt it? Likely, it was because food deliveries from "mainland" Russia were erratic and plagued with problems, leading to frequent shortages. Poor nutrition must have reduced the health of the population and increased the death toll. There are no reliable records on how many died during the Azov colonization, but estimates indicate the death toll was in the range of 15,000-25,000. This put the human toll of the project up there with Stalinist forced-labor projects of the 1930s, but Pyotr's Russia had only about 14 million people in 1700, as compared to Stalin's Soviet Union with about 160 million in 1930. (However, Pyotr's Russia only had two deadly forced-labor projects, while Stalin's USSR had many.)

Was the Azov project worth it? Certainly not for the common people. Those at Azov suffered and died, while those in the rest of Russia derived no benefit from Azov. But, was it worth it for the Russian state? Pyotr thought so. When he visited Taganrog in 1709, he remarked, "In this place where ten years ago we just saw open country, with God's help now we find a fine town with a harbor." In just two years, however, the entire project was lost through no fault of its own. Pyotr went to war with the Ottoman empire in 1710, only to get his army encircled and decisively defeated in 1711. The peace treaty that year required Russia to withdraw from the entire Azov region, to return the Azov fortress to the Ottomans, and to destroy all other fortifications the Russians had built there. Other than Azov fortress, the Russians tried to destroy or evacuate everything they had built over 15 years. Warships too large to sail up the Don River were sold to the Ottomans, cannons and all. Pyotr had lost his access to the Sea of Azov and his base for further expansion in Black Sea region. Russia would not return to the area for decades. Azov fortress was now Azak again and remained so until 1736, when Russian forces took it again. It wasn't until 1769 that Russia reconquered the ruins of Taganrog and refounded the city, port, and naval base there.

The Azov Project is sometimes called Pyotr's greatest mistake, but it really wasn't. The mistake was Pyotr's poorly led campaign against the Ottomans. If this needless war had been better led or avoided entirely, the Azov region likely would have remained Russian, and development would have continued. The human cost of the Azov Project was horrendously high, but so was the human cost of the Sankt-Peterburg project (forced labor in conditions resulting in many deaths), yet this is not called a mistake of Pyotr.

Fortress of Azak/ Azov circa 1764 ("Plan D’Azak ou Azoe" ["Plan of Azak or Azov"] from Le Petit Atlas Maritime Recueil De Cartes et Plans Des Quatre Parties Du Monde [The Small Maritime Atlas, Collection of Maps, and Plans of the Four Parts of the World]; Jacques Nicolas Bellin; 1764)

* The Russian musketeers were the Streltsy. They were originally formed by Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrifying) around 1550 as his elite troops and bodyguard, recruited from commoners. Over time, they became a closed, hereditary class. Service as Streltsy passed from fathers to sons without regard to ability or interest. Accordingly, Streltsy military skills declined. In peacetime, they were used as city guards, police, and firefighters and as border guards in the countryside. The Russian government often did not pay the Streltsy all that it owed them, so in addition to their official duties they also supported themselves as craftsmen, merchants, and farmers, further eroding their military effectiveness. In war, they campaigned with the Tsar's other troops but were now of limited effectiveness. The more impoverished Streltsy became increasingly discontent and prone to join revolts and peasant uprisings. In 1698, about 2,300 Streltsy (out of at least 55,000) revolted because of poor treatment and lack of food. Their fatal error was to try to replace Pyotr with his half brother, Ivan V. Their revolt was put down and Pyotr severely punished them, with torture and executions. The "underage musketeers" sent to Azov were the sons of these Streltsy rebels. The revolt also signaled the beginning of the end for all the Streltsy, as Pyotr officially abolished the Streltsy class. Most actually remained in Pyotr's service due to his need for troops to fight his many wars. Over the coming decades, though, the more militarily-capable Streltsy were absorbed into the Russian army, and most of the rest became ordinary civilians.